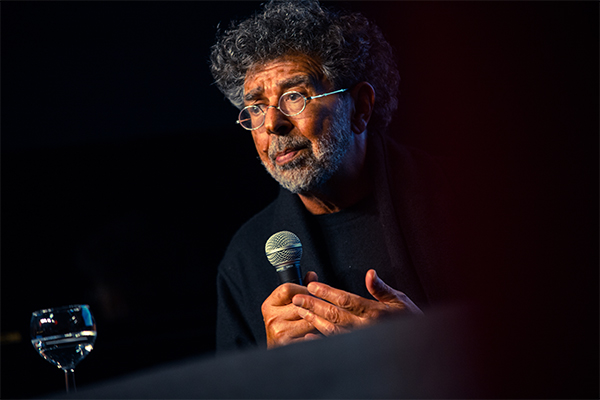

Master class by Gabriel Yared

PostED ON OCTOBER 15 AT 6:36 PM

"You don’t mind?" During an exciting master class, where he performed his most famous compositions on the piano, Gabriel Yared broke down for the audience his unique working method, with ever-present passion.

Copyright Institut Lumière / Loic Benoit

On his advantage of expressing himself through the cinema:

I've always wanted to be a composer. This domain presented itself to me. In me, there are many things that are alive: my past in Lebanon, my taste for black music, jazz, a past penchant for the Beatles, a passion for Charles Trenet, who is a great melodist ... I have also liked ethnic music. All these things put together - plus my interest in the music of Robert Schumann, then for Bach, Mozart, Ravel - all this is alive within me. It was cinema that allowed me to express this polygamy of taste at the very beginning. After the Oscar, I was confined to a style. Cinema opened that door to me thanks to Godard, until I met Anthony Minghella. The music I love is so vast that I am grateful to the cinema for allowing me to express it. The influences are audible, visible, but I don't care about influences. You have to let the music live inside you.

On his ‘falling into’ to the cinema:

I was self-taught. I hadn't taken a writing class. I hadn't learned the rules that allow someone to build what they draw, musically. I decided to take a two-year sabbatical to learn, because it made me self-conscious and insecure. I found a retired teacher who taught me about the counterpoint and then the fugue. I took this course, and after two years I came back. I was armed with this, and I had the chance, thanks to Jacques Dutronc, to meet Jean-Luc Godard. It was his first film in a long time. I met him and saw this man who still spoke to me about orchestration when I had spent two years away from it. I said no to him. Karmitz, who was there when we met, told me: you're crazy, it's Godard! A few days later, I received a note from Godard who said: I really enjoyed our conversation. He liked my sincerity. I found his way of dissecting the heart of the music fascinating. He is aware. He is interested in all the ‘co-directors’ of films: the composers, writers, etc. My greatest luck has been to start with Jean-Luc Godard. I really liked this man. He is a great thinker who turned my life upside down.

On meeting Jean-Jacques Beineix:

It is consistent with my journey as a composer. He came up to me and asked me to do the music for The Moon in the Gutter (1983) beforehand, so that we could play it on the set, before filming. He needed a tango, a waltz, and the theme of the movie. They then shot the film based on my models. It was of great importance, especially for the actors. Having music in your ears changes the perspective. The great thing about Beineix is that he asked me for a lot of different things. It’s like he’s asking me to let myself go. Even though the film was a flop, I felt that I had taken a huge step towards cinema. It really struck me. It’s the suggestive images that inspire me, not the embodied ones. Music is a character in a film: in order for it to speak, you have to give it space. Beineix has shown the same interest here. The composer who arrives a month before the shoot cannot be a co-creator. There is no rule, but when we practice this approach... it is not an approach by the way, but a method. I might be masochistic, but I liked spending time there. To give back to the music what it gave me. I am not interested in covering, in patching up spaces.

On transmission:

Often, when I meet young composers, I leave my scores open. I tell them, don’t admire them contentedly. We have to show them what they admire in order to demystify it, to explain how it was done. All of these things should be in a film soundtrack library and make it evolutive, so they don't blindly admire film score composers. And if someone plagiarises from me, so much the better, at least it will force me to come up with something new.

On his collaboration with Anthony Minghella:

For The English Patient (1996), Anthony Minghella came to chat with me for three days on Monks Island, where I was staying. He begged me to compose the theme of the film beforehand to convince the producer, who wanted an American composer. I had two or three months to create the theme. Like a good student, I played it for the producer, and he said to me, “You’re hired”. For The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999), I had finished writing the score, when I wrote, for my own pleasure, an accompaniment to the theme. I sent in a demo, and one day Anthony called me, saying "We found a location for this." He used it for a scene that I had already written the music for, but which was a bit sappy. It's amazing how the coincidence of things can happen when you don't do it on purpose.

Copyright Institut Lumière / Loic Benoit

On his journey after Minghella's death:

Minghella was a brother in arms, which made me feel free. When he passed away, I wondered what to do. I didn’t want to be industrious. I took a year off. I had found my companion and I did not find him later. To work with a composer is to understand him, to know him. The salvation of the image is in music. I like the rhythm, and all I am offered to do is themes. Now, I want to go back to basics! The problem for me is being catalogued. I am a rhythmist. I did this with Beineix in Betty Blue. Since then, nothing. Wake up, guys!

When his composition was dismissed from Troy by Wolfgang Petersen:

I had been writing for a year and a half. We were at Abbey Road during the recording and the director called his wife to play the theme for her and tell her how good he thought it was. They left and I was contacted to tell me that I was fired while I was mixing the music. I had been very sincere, very honest about this job, but it was good that it happened to me. I was badly injured and had had a stroke. When I saw the result, I felt happy that I did not contribute to this mess. After that, I didn't want to work in Hollywood anymore. What is happening to me makes me very happy. I am not looking to be somebody.

Interviewed by Benoit Pavan