The Money Order, a bittersweet reflection of Senegalese society

PostED ON OCTOBER 15 AT 11:45 AM

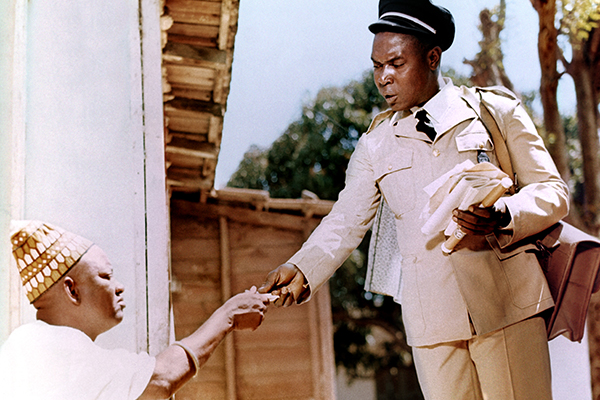

Considered one of Ousmane Sembène's masterpieces, The Money Order (1968) paints an uncompromising - but not humourless - portrait of the new Senegalese bourgeoisie that emerged in 1960 with the country's independence. Alain Sembène, the son of the filmmaker who died in 2007, looks back on the genesis of this bittersweet comedy, restored by Studiocanal.

In what context did Ousmane Sembène, your father, make The Money Order?

In 1968, he had his first big movie success with Black Girl… (1966), which brought him international fame. It was the first time that an African from French-speaking black Africa had made a film on Senegalese territory. My father was first known as a novelist, notably thanks to God’s Bits of Wood (1960). The Money Order is an adaptation of an eponymous novel he published with Éditions Présence Africaine in 1965. In the book, he evokes African society through the prism of his Senegalese counterpart. My father had a fairly critical view of it and in the film, he denounces the mentalities of the time and the workings of the administration. When I was younger, I saw this film as a comedy. Over time, The Money Order seems closer to a tragedy, because it shows, above all, how cruel society is in Senegal. In his films and his books, my father knew how to portray human nature with brio.

How was the film received upon release?

Its reception was mixed. On one hand, it was well regarded by Senegalese society as a whole. We can even say that it caused a great stir and that it continues to enjoy a good reputation there. On the other hand, it put the Senegalese authorities a bit on edge. My father had always had a very difficult relationship with power. I was educated in the Soviet Union, and in the 1980s, I met the Senegalese ambassador in Moscow. We talked about my father's works and he lamented that they gave Senegal a bad image.

Most of his other films have also displeased the authorities in power...

Indeed. Relations with the government of Léopold Sédar Senghor have always been bad. The Money Order was tolerated, but other films created a stir. In Xala/The Curse (1974), he caricatured the president. In his next feature film, Ceddo/Outsiders (1977), he tackled the introduction of the Catholic and Muslim religions. The film was banned for almost ten years. My father was rough around the edges, and said what he thought out loud, especially through his works. The authorities obviously never liked it.

What impact has The Money Order had on what it denounces?

None. On the contrary, the situation is worse now. The film proved my father right. What is extraordinary is that, from a simple story, he was able to describe the dysfunctions of Senegalese society. There is not one of his feature films that has not been successful and marked the country in some way or another.

A word about the shooting and restoration of the film?

The Money Order is a Franco-Senegalese collaboration. My father was still shooting with the same team, made up of Senegalese people and two French people, including Paul Soulignac, who did the of cinematography. The takes were dubbed; one was in French and the other in Wolof. The French version was eventually dropped because he was not happy with its rendering. It was never edited, and the rushes were never found. The restoration of the film was carried out by the Cineteca di Bologna. Two films by my father, a short film (Borom Sarret/The Wagoner, 1963) and Black Girl had previously been restored by the Martin Scorsese Foundation. All his films are currently being restored by Criterion.

Interview by Benoit Pavan