Viggo Mortensen, On the road

PostED ON OCTOBER 7 AT 3:26 PM

Viggo Mortensen lives multiple lives: A poet who remembers his encounters, a photographer of intense landscapes in chiaroscuro, a musician, a figurative painter in search of abstraction, a fan of the Argentinian football club San Lorenzo, an admirer of the genius of absurd and cruel drawings by Marcel Dzama, even penning the introduction to Dzama’s book, The Berlin Years, citing Tarkovski: "Artists exist because the world is imperfect” and he is an actor and a director, a guest of honour at this year’s Lumière festival.

Copyright Columbia / DR

In the thirty-six years of his career and in over fifty films, the lithe body and compliant hair (yielding itself to a plethora of styles) of Viggo Mortensen have taken on a diversity of identities. He has portrayed an Amish farmer, an American yakuza, Lucifer, the attentive lover of Nicole Kidman (The Portrait of a Lady, Jane Campion, 1996), Demi Moore’s relentless training officer (G.I. Jane, Ridley Scott, 1997), or a brilliant, wheelchair-bound traitor dealing with a sadistic Al Pacino (Carlito’s Way, Brian De Palma, 1993). Mortensen has been all that, and much more; the actor lends his razor-chiselled face, perfect for close-ups, where he appears willingly dangerous in independent production films that depict a "white trash” America, disarming and ruthless.

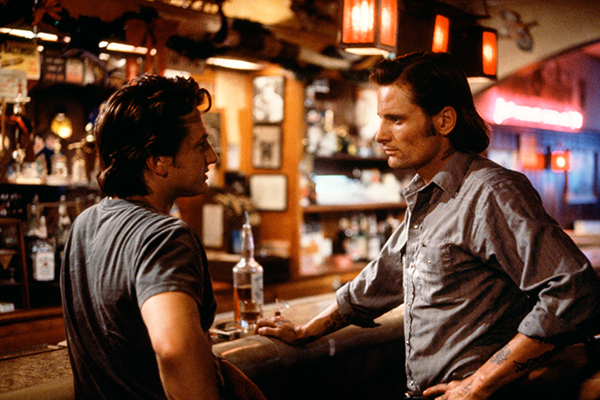

Mortensen's finest incarnation of these stories with deep American roots is The Indian Runner (1991). Sean Penn’s first foray into filmmaking had its genesis in a song by Bruce Springsteen (another great explorer of American outsiders), entitled Highway Patrolman: "Franky ain’t no good... I catch him when he’s strayin’, like any brother would”. Inspired by these words, Penn wove the tale of a conflicted, yet loyal relationship between two opposite brothers: Joe the sweet, and Frank the fool. Heavily tattooed, tortured by an American history that has scant interest in dealing with its veterans, Mortensen embraced a Frank, crushed by his own aggressiveness, lacking the will to control anything. This is the actor's first landmark role, but not his last trip to the land of violence.

Copyright Bender-Spink Inc. /DR

With the decade of the 2000s, Mortensen becomes the consenting creature of the experiments of the charming filmmaker with a penchant for twisting bodies and minds: David Cronenberg. For these films, the actor initially introduces mild-mannered characters, who are subsequently capable of unprecedented and professional brutality, which both surprises and saddens him. Mortensen is the danger despite himself, a loving father, a good husband, a kind restaurateur, but who turns out to be a more ferocious killer than the Devil in David Cronenberg's splendid A History of Violence (2005). The Canadian filmmaker uses Mortensen's soft voice, shyness, unobtrusive walk and kindness to transform him into an American who doesn't realize that carrying a gun today is an act of unhealthy porosity.

On the other hand, endowed with a sword (which he wields with a highly developed sense of choreography in historical films), Mortensen imparts legit heroes with a thrilling, adventurous fervour. Always for the entire planet, he plays the noble Aragorn of the trilogy of The Lord of the Rings (Peter Jackson, 2001, 2002, 2003) and the cunning Alatriste (Agustin Diaz Yanes, 2005). Such chivalrous roles seem predestined for Mortensen, the artist who founded a small publishing house called Perceval Press. Perceval is the knight devoted to the quest for the Holy Grail, the one who naturally believes in the pursuit and will fight, exactly like the teacher in Far from Men (David Oelhoffen, 2014), in the midst of the Algerian war, as seen by the committed spirit of Albert Camus. It is also by implication that Mortensen transforms himself into a burly man of the 60s, a strait-laced driver with a mocking smile, who will learn about tolerance through his contact with an African American artist confronted with racism, in the very effective Green Book (Peter Farrelly, 2018).

Copyright Estudios Picasso / DR

"You have to dream to be able to get up in the morning", said the excellent Billy Wilder. Mortensen is certainly aware of this because the last "Mortensen dimension" (perhaps the deepest?), is that of the dream of another, a family. It is evocative in the actor's paintings, but also in travel films where time no longer counts, very special experiences, sometimes tinged with bohemia, that are the hippie Captain Fantastic (Matt Ross, 2016), the prodigious Jauja (Lisandro Alonso, 2014), and the very recent tragic and poignant Falling (2020), which is the first directorial achievement by Mortensen, who also stars in the film. They are all traumatised heroes with a full heart, marked by the impossible dream of making peace with one of their family members: their wife, their daughter or their father. A secretive and most private dream… revealed. A real challenge for a humble and unassuming artist.

Virginie Apiou

Viggo Mortensen

An encounter with Viggo Mortensen Sunday, October 11 at Comédie Odéon at 3:30 p.m.

He will also introduce

The Indian Runner Sunday, October 11 at the Lumière Institute at 2:45 p.m.

Falling Sunday, October 11 at Pathé Bellecour at 5:30 p.m. and Monday, October 12 at the Lumière Institute at 8:45 p.m.

A History of Violence Sunday, October 11 at the Zola / Villeurbanne at 7:30 p.m.

Captain Fantastic Sunday, October 11 at the UGC Ciné Cité Confluence at 8:30 p.m.

Green Book Monday, October 12 at Cinéma Comœdia at 10:45 a.m.

Far from Men Monday, October 12 at Lumière Terreaux at 2:45 p.m.